By Norman Fischer

http://happydays.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/07/for-the-time-being/

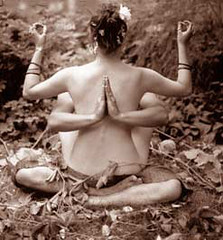

I recently returned from a week-long Zen meditation retreat on the Puget Sound. I am a Zen Buddhist priest, so a meditation retreat isn’t exotic to me: it’s what I do. But this one was particularly delightful. Sixty-five of us in silence together for a week, as great blue herons winged slowly overhead, swallows darted low to the ground before us as we walked quietly on the open grassy space between the meditation hall and the dining room. Rabbits nibbled on tall grasses in the thicket by the lake. The sky that far north is glorious this time of year, full of big bright clouds that can be spectacular at sunset — which doesn’t happen until around 10 p.m., the sky ablaze over the tops of the many islands thereabouts.

So yes, it was peaceful, it was quiet, it was beautiful, and nice to be away from all telephones and computers, all tasks and ordinary demands, all talking, all purposeful activity. The retreat participants are busy people like everyone else, and they appreciated the silence, the natural surroundings, and the chance to do nothing but experience their lives in the simplest possible way.

As most people know, a Zen meditation retreat is not a vacation. Despite the silence and the beauty, despite the respite from the busyness, the experience can be grueling. The meditation practice is intense and relentless, the feeling in the hall rigorous and disciplined. We start pretty early in the morning and meditate all day long, into the late evening. It can be uncomfortable physically and emotionally. And some people find it hard not to talk at all for a week. So, what’s in it for them?

If you live long enough you will discover the great secret we all hate to admit: life is inherently tough. Difficult things happen. You lose your job or your money or your spouse. You get old, you get sick, you die You slog through your days beleaguered and reactive even when there are no noticeable disasters — a normal day has its many large and small annoyances, and the world, if you care to notice, and it is difficult not to, is burning.

Life is a challenge and in the welter of it all it is easy to forget who you are. Decades go by. Finally something happens. Or maybe nothing does. But one day you notice that you are suddenly lost, miles away from home, with no sense of direction. And you don’t know what to do.

The people at the retreat were not in crisis — at least no more than anyone else. I know most of them pretty well. They are people who have made the practice of Zen meditation a regular part of their daily routine, and come here not to forget about their troubles and pressures, but for the opposite reason: to meet them head on, to digest and clarify them. Why would they want to do this? Because it turns out that facing pain — not denial, not running in the opposite direction — is a practical necessity.

This week I talked about time, using as my text the 13th century Zen Master Dogen’s famous essay “The Time Being,” a treatise on the religious dimension of time.

Dogen’s view is uncannily close to Heidegger’s: being is always and only being in time; time is nothing other than being. This turns out to be less a philosophical than an experiential fact: to really live is to accept that you live “for the time being,” and to fully enter that moment of time. Living is that, not building up an identity or a set of accomplishments or relationships, though of course we do that too. But primarily, fundamentally, to live is to embrace each moment as if it were the first, last, and all moments of time. Whether you like this moment or not is not the point: in fact liking it or not liking it, being willing or unwilling to accept it, depending on whether or not you like it, is to sit on the fence of your life, waiting to decide whether or not to live, and so never actually living. I find it impressive how thoroughly normal it is be so tentative about the time of our lives, or so asleep within it, that we miss it entirely. Most of us don’t know what it actually feels like to be alive. We know about our problems, our desires, our goals and accomplishments, but we don’t know much about our lives. It generally takes a huge event, the equivalent or a birth or a death, to wake up our sense of living this moment we are given – this moment that is just for the time being, because it passes even as it arrives. Meditation is feeling the feeling of being alive for the time being. Life is more poignant than we know.

Dogen writes, “For the time being the highest peak, for the time being the deepest ocean; for the time being a crazy mind, for the time being a Buddha body; for the time being a Zen Master, for the time being an ordinary person; for the time being earth and sky… Since there is nothing but this moment, ‘for the time being’ is all the time there is.”

For seven days that week I spoke about this in as many ways as I could think of, silly and sometimes not silly, and for seven days 65 silent people listened and took Dogen’s words to heart.

We want enjoyment, we want to avoid pain and discomfort. But it is impossible that things will always work out, impossible to avoid pain and discomfort. So to be happy, with a happiness that doesn’t blow away with every wind, we need to be able to make use of what happens to us — all of it — whether we find ourselves at the top of a mountain or at the bottom of the sea.

Sunday, August 9, 2009

Enjoy The Effort No Matter What The Effect

Swami Sukhabodhananda

We have many desires and targets. We dont always get what we want. Some of us are happy with what we get, and others remain dissatisfied. Still others dont give up; they keep trying. Which approach would be the right one

I will recommend another approach. You can have a desire. Put in your best effort to fulfil it. But make sure you enjoy the effort rather than its fruits. There are those who make the effort grumbling and are happy only when the desire is achieved. There are others who exhaust themselves making the effort to such a degree that they have no strength or enthusiasm left to enjoy the fruit. My method is: Enjoy the effort no matter what the effect.

My approach is to celebrate the march towards the destination . If the destination is reached, we will be happy. Even if it is not reached, nobody can take away the sense of thrill at having run the race, the delicious fatigue felt along the whole body. My happiness is derived not from reaching a goal, but from the struggle i wage as part of my attempt at reaching it. I am engaged in talking to you now. Suppose i feel i will be happy only if you give me a thundering ovation when i conclude my lecture. That means i am not fully enjoying my teaching, rather, my mind is set on a particular goal. That very concern may prevent me from giving my best to my teaching and thus act as a barrier to my attaining the goal.

Playing football is one kind of joy, winning is another kind. The problem is we identify joy exclusively with winning. Classical musicians are so absorbed in their performance that for all practical purposes, they are unmindful of the audience, the applause at climactic points, or the money they will receive from the organisers at the end. What they enjoy is their involvement in bringing their art alive, not the end result in the form of ovation or payment. So enjoy the process. Enjoy the travel. Enjoy the endeavour.

Ensure that you will be working smart, not just hard. Dont go fishing in the bathtub. Dont try to work up lather in a running stream. Instead, fish in a stream, and work up lather in a bathtub. Set and evaluate your goals, estimate the quantum and quality of efforts to be invested in attaining the goals, calculate the ROI (return on investment) quotient carefully, and then, if you are convinced the ratio is as satisfactory, go ahead and work towards your goals. That is smart work, intelligent effort. Failure is a fact of life. In all competitive contexts as in sports, for example, one side has to lose. So why not enjoy the effort rather than exult at success or mope at failure I think it is better mental discipline to celebrate the successes rather than brood on the losses. It is definitely a healthier strategy for the future for anyone wishing to continue in competitive endeavours.

There is also a spiritual lesson in every failure. Failures are necessary to remind people of their essential human vulnerabilities . An unbroken string of successes can create pride and a sense of invincibility about oneself in a high achiever. Remember the bragging, I am the greatest that comes out of the mouths of wrestlers and boxing stars As the common maxim goes, such pride always precedes a great fall. Surrendering to the Lord is an act of bhakti devotion, and surrender happens only in a spirit of humility.

We have many desires and targets. We dont always get what we want. Some of us are happy with what we get, and others remain dissatisfied. Still others dont give up; they keep trying. Which approach would be the right one

I will recommend another approach. You can have a desire. Put in your best effort to fulfil it. But make sure you enjoy the effort rather than its fruits. There are those who make the effort grumbling and are happy only when the desire is achieved. There are others who exhaust themselves making the effort to such a degree that they have no strength or enthusiasm left to enjoy the fruit. My method is: Enjoy the effort no matter what the effect.

My approach is to celebrate the march towards the destination . If the destination is reached, we will be happy. Even if it is not reached, nobody can take away the sense of thrill at having run the race, the delicious fatigue felt along the whole body. My happiness is derived not from reaching a goal, but from the struggle i wage as part of my attempt at reaching it. I am engaged in talking to you now. Suppose i feel i will be happy only if you give me a thundering ovation when i conclude my lecture. That means i am not fully enjoying my teaching, rather, my mind is set on a particular goal. That very concern may prevent me from giving my best to my teaching and thus act as a barrier to my attaining the goal.

Playing football is one kind of joy, winning is another kind. The problem is we identify joy exclusively with winning. Classical musicians are so absorbed in their performance that for all practical purposes, they are unmindful of the audience, the applause at climactic points, or the money they will receive from the organisers at the end. What they enjoy is their involvement in bringing their art alive, not the end result in the form of ovation or payment. So enjoy the process. Enjoy the travel. Enjoy the endeavour.

Ensure that you will be working smart, not just hard. Dont go fishing in the bathtub. Dont try to work up lather in a running stream. Instead, fish in a stream, and work up lather in a bathtub. Set and evaluate your goals, estimate the quantum and quality of efforts to be invested in attaining the goals, calculate the ROI (return on investment) quotient carefully, and then, if you are convinced the ratio is as satisfactory, go ahead and work towards your goals. That is smart work, intelligent effort. Failure is a fact of life. In all competitive contexts as in sports, for example, one side has to lose. So why not enjoy the effort rather than exult at success or mope at failure I think it is better mental discipline to celebrate the successes rather than brood on the losses. It is definitely a healthier strategy for the future for anyone wishing to continue in competitive endeavours.

There is also a spiritual lesson in every failure. Failures are necessary to remind people of their essential human vulnerabilities . An unbroken string of successes can create pride and a sense of invincibility about oneself in a high achiever. Remember the bragging, I am the greatest that comes out of the mouths of wrestlers and boxing stars As the common maxim goes, such pride always precedes a great fall. Surrendering to the Lord is an act of bhakti devotion, and surrender happens only in a spirit of humility.

Saturday, May 23, 2009

Tuesday, January 6, 2009

Religion

'Spirituality is a particular term which actually means: a dealing with intuition. In the theistic tradition there is a notion of clinging [to] a word. A certain act is regarded as displeasing to a divine principle; a certain act is regarded as pleasing the divine ... whatever. In the tradition of non-theism however it is very direct - that the case histories are not particularly important. What is actually important is here and now. Now is definitely now. We try to experience what is available there ... on the spot. There's no point in us thinking that a past did exist that we could have now. This is now. This very moment. Nothing mystical, just 'now', very simple, straightforward. And from that now-ness, however, arises a sense of intelligence always that you are constantly interacting with reality one by one. Spot by spot. Constantly. We actually experience fantastic precision always. But we are threatened by the now so we jump to the past or the future. Paying attention to the materials that exist in our life - such rich life that we lead - all these choices take place all the time ... but none of them are regarded as bad or good per se - everything we experience are unconditional experiences. They don't come along with a label saying 'this is regarded as bad' or 'this is good'. But we experience them but we don't actually pay heed to them properly. We don't actually regard that we are going somewhere. We regard that as a hassle. Waiting to be dead. That is a problem. And that is not trusting the now-ness properly. What is actually experienced now possesses a lot of powerful things. It is so powerful that we can't face it. Therefore we have to borrow from the past and invite the future all the time. And maybe that's why we seek religion. Maybe that's why we march in the street. Maybe that's why we complain to society. Maybe that's why we vote for the presidents. It's quite ironical ... very funny indeed.'

-Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

-Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)